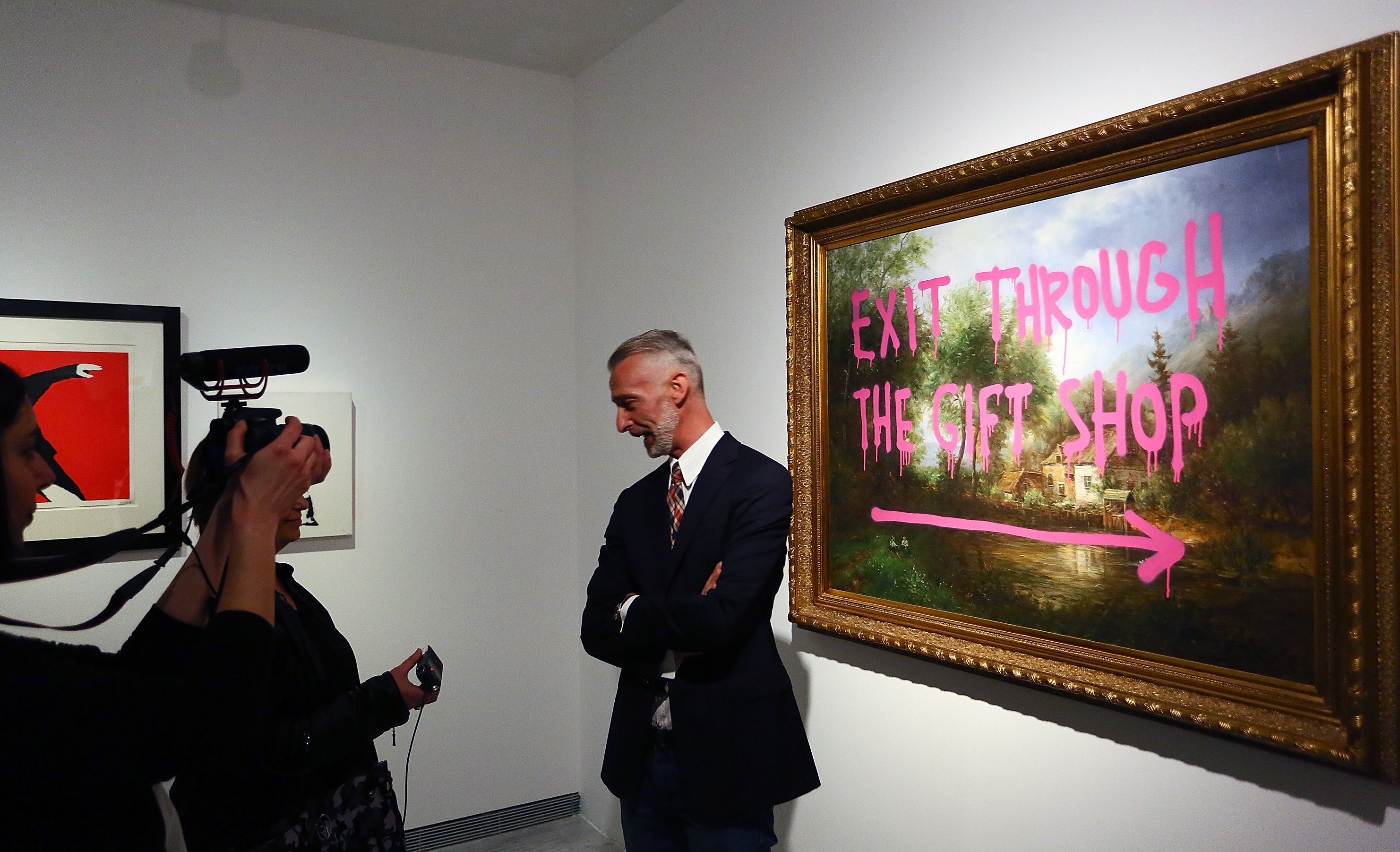

Overview

"War, Capitalism and Liberty": An exhibit of work by the English street artist Banksy in Rome, May 2016. Such work has become part of the global art market.

(Ernesto Ruscio/Getty Images)After majoring in English literature, Larry Gagosian started his career in the 1960s selling framed posters of ocean vistas in Los Angeles. "Schlock," Gagosian described them recently. "I could have been selling anything; it could have been belt buckles. It was just something to sell."1

He graduated to promoting prints and higher quality work, and eventually some of the pictures were valued in the millions. His global art venture brings in an estimated $1 billion in annual revenue with a roster of artists that includes Pablo Picasso, Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst and Alberto Giacometti, plus a retail shop that sells Andy Warhol Campbell Soup candles for $60 apiece.

His 15 galleries in Europe and the United States and one in Hong Kong give him broad reach to sell art and promote his coterie of creators. He and other global gallery owners have set up shop in Hong Kong to capitalize on the growing wealth in China and to recruit local talent.2 And Gagosian's galleries in Athens and Paris give him outlets to show works by artists who are represented by other galleries in New York.3 "The sun never sets on my gallery," he said.4

In many ways, Gagosian's empire demonstrates important trends in the art market. Artists and gallery owners have become celebrities, brands and big businesses. More people have invested in art in hopes that it will appreciate in value. Galleries, artists and collectors, following the lead of many businesses, have become more diverse and global, creating a host of opportunities and issues. Digital art and online galleries are growing rapidly, while small independent galleries and shops that have not adapted to the changes are dying.

Starting about 30 years ago, Chinese and Japanese artists began selling their work in galleries in Los Angeles, San Francisco and elsewhere. "Chinese contemporary art got very hot," says John Zarobell, a University of San Francisco assistant professor writing a book on global art trends. "Then Indian and Russian art got hot. All these other artists were coming from all over the world and getting all the attention." Galleries that once focused on local or regional artisans felt they needed to add international artists to appear cosmopolitan and stay competitive.

Free-trade agreements opened up opportunities to bring in affordable craft items and fine art made in Vietnam, China and elsewhere, but 30 percent of independent galleries and shops have closed because they could not get credit lines in the 2007-09 recession, says Wendy Rosen, who started the American Made Show, a trade exhibition for U.S. products, in Baltimore in 1981.

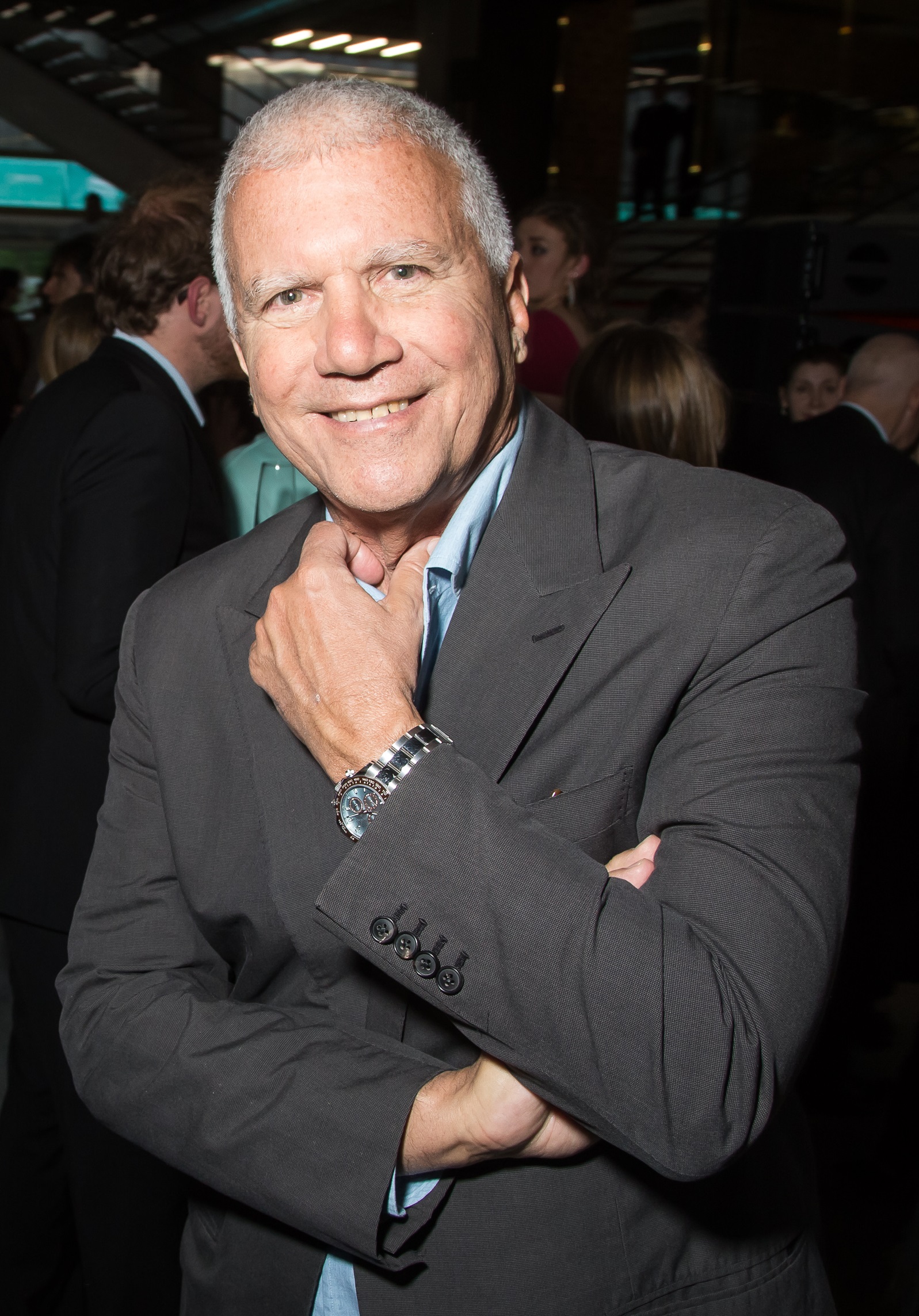

Art dealer Larry Gagosian at a dinner celebrating a museum opening in Moscow in 2015.

(Victor Boyko/Getty Images)For all its reach and influence, Gagosian's empire depends on market forces that mix the economics of supply and demand, greater disposable income among the world's wealthiest individuals, greed, desire and the lubrication provided by parties serving French Champagne. "I believe in the popularizing of art. But when you get right down to it, it's a bit of an elitist world," Gagosian said.5

Art flourishes when the rich get richer and when new museums, often funded by wealthy patrons, open in places like China, South America or Africa, Zarobell and other experts say. They seek profit and status as much or more than timely or beautiful pieces, and some seek to leave a legacy as art patrons who rank with famous collectors such as Peggy Guggenheim, whose modern art collection is housed in a Venice museum, or Charles Lang Freer, an industrialist whose huge collection of Asian art is now part of the Smithsonian Institution.

Art prices are particularly sensitive to the fortunes of the rich, researchers have found, although stock market valuations and economic cycles also affect prices.6

An estimated $64 billion in art was sold in 2015, down about 7 percent from the previous year. The U.S. market, the world's largest, continued to grow, but the art world is highly polarized.7 China ranks second in global art auction sales, and for a couple of years was the top market.8

Some experts suggest that the art market valuation would be far larger if data could be gathered from all the independent sales, small artisan markets and tourist spots.

The global art market consists of paintings and sculpture, but also art prints, antique tea sets and furniture, quilts and fiber work, even graffiti by Banksy, the English street artist. This diversity creates several strata: artists selling monthly in a New Orleans park, weekend artisans who sell to DIY friends over local craft beer, major auction houses marketing trophy pieces, and small galleries in places like Buenos Aires, Beijing and Bangalore.

The art market has set record prices repeatedly in recent years, yet it may be a bubble starting to deflate--or burst--as China's slow growth and global economic slowing quell the huge spike in prices.

Sales in London, which ranks as the world's second largest art auction market after New York, were weak in December 2015, and buyers were more selective. And terrorism threats may deter buyers from attending European sales and major art events.9

"The art market is overheated right now, and it could crash and then everyone could moan," says Carolyn Edlund, an arts and business educator and founder of Artsy Shark, a blog that promotes artists and business skills and that will add an online art gallery this summer.

The global art market employs an estimated 6.7 million people at businesses ranging from major companies to small galleries, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

The creative sector, which includes advertising, architecture and television as well as the visual arts, accounts for about 3 percent to 6 percent of total employment in many developed countries.10 In a few U.S. cities, such as San Francisco, Denver, Ann Arbor, Mich., and Washington, D.C., the creative economy represents one in seven jobs in 2013.11 (The creative economy includes software, television and film, music, publishing and advertising.) More Americans identify their primary job as artist than as lawyer, doctor, farmworker or police officer.

To read the article http://www.artspecifier.com/photos/the-global-art-industry.pdf